Before reading this post I think it’s best if you go grab your thinking cap, your art appreciation goggles, and possibly a snack depending on your hunger level at the moment.

It may be slightly boring or potentially not entertaining, but I would really love to write a recap of the Picasso exhibit I viewed on Monday. As most of you will not be visiting Milan before January (but I do love surprises!), I feel that I must share, to the best of my abilities, the exhibit’s content. Picasso is obviously a well known painter. Of course I enjoy viewing his artwork, but I’ve never been head-over-heels about his story or pieces. The pleasure of viewing generally comes from excitement of seeing such famous and well-discussed art works. Previous to this exhibit, probably my favorite thing about Picasso is an anecdote I heard somewhere stating that at one point in life, Picasso would go to the grocery store, select his items, and instead of paying for his food, he would instead draw a doodle on the back of the receipt, thereby making the paper more valuable that his actual food. Sounds like a good deal to me. The Italian cashiers already hate the American customers, I wonder what they would do if I tried to pull a Picasso on them!

What? You won’t accept my scribble for payment? Well, sorry I don’t carry cash.

(And I most certainly don’t carry exact change. Why is this such a big deal here?)

The Palazzo Reale exhibit really opened my eyes to who Picasso was and what he was capable of, which was apparently everything. My new favorite thing about Picasso is that he worked in so many different mediums; painting, collage, sculpture, photography. It was wonderful to experience the vast array of his experimentation.

Oh wait! Crud! I lied.

This is my new favorite thing about Picasso

He hangs out at the bull fights with his son’s hand in his mouth.

But, professionally speaking, I was very impressed with what I learned about the evolution of his artwork.

I have yet to do additional research, but this is what I gathered from the written portion of the exhibit.

(Thank you for the English versions that were given as much importance as the Italian).

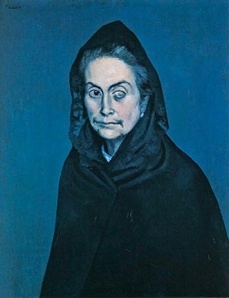

At the beginning of his career, Picasso began exploring artistic representation that strayed from the traditional academic realism of the time. In the Blue Period (1901-1904) subject matter was simplified in both style and color. Best known from this stage and accurately representative of both the name and characteristics of the Blue Period is Picasso’s Celestina.

- La Celestina 1904

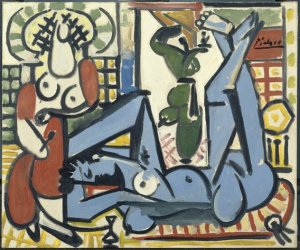

- Moving forward into the Pink Period, Picasso began to experiment with primitive expression. Many factors were at play in this time of Picasso’s life between 1904 and 1909, assisting the development of his artistic participation in Cubism. A formative quote from French Impressionist Cezanne states, “Treat nature by means of the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything brought into proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point.” A similar thought process was applied in the construction Picasso’s works during the Proto Cubism phase, breaking subject matter into various two dimensional planes and then painting them with three dimensional qualities. Picasso was also introduced to African and Oceanic art in 1907, further influencing and enhancing his inspiration for the geometric. I believe Three Figures Under a Tree to demonstrate the ideas and practices of Picasso contemporary to his Pink Period work.

During the surprisingly short period in which Picasso has been declared a participant of Cubism, 1910-1912, he made a serious impression within the art realm. Both Picasso and Braque share the limelight as faces for the Cubist Movement, distorted and geometric faces as it were. They worked to present the complexity of visual reality within a muted color palette. Picasso portrayed volumes opened up into their outlines. He united successive visual planes and displayed the internal structure of painted subject matter, resulting in an abstracted concluding image. As you can observe in his Man With a Guitar, a traditional subject is suggested but very much abstracted through the representation of planes. Perhaps you would not even notice the overall figure if it were not for the painting’s title.

Continuously advancing and changing, Picasso next moved into his Classical Period from 1915-1924. Upon viewing the artworks, I had trouble understanding how an artist moves from such angular and abstracted geometry to the content of the Classical Period, which instead favors sinuous lines and photographic articulation. At such a point, this particular observer realized she had to move past simply viewing artwork and pay attention to surrounding factors that were paving Picasso’s path. The end of WWI, a marriage, the birth of a son, a return to order, a trip to Rome and subsequent study of ‘the classics’; all of these influences led to works such as Portrait of Olga in Armchair.

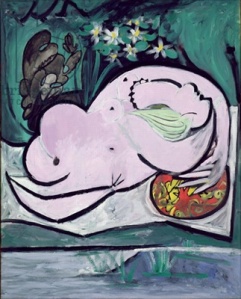

Potentially more understandable than the transition from Cubism to Picasso’s Classical Period, is the following development from Classical into Surrealism, 1924-1935. From my understanding, Surrealism seems to combine both the appreciation of the curvilinear present in the Classical Period with the distortion of planes within Cubism. Also present within his new painting style is a significant lack of gravity, leading to the painted figures of this period being described as ‘disturbing’ and ‘languid’. I could certainly get on board with this description as most of the displayed images looked similar to his Nude in the Garden. I think you would definitely need a lack of gravity to recreate a pose similar to this.

As the second World War began to influence to the lives of European occupants, Picasso’s art began to contain significant political relevance. His pieces bore witness to the developing history and was frequently supportive of the Spanish Republican party. Visually there was a continuing return to Cubism, as he depicted intersecting two dimensional planes, frequently containing face subject matter. From 1935-1951, Picasso used his artwork to request that people think of their personal decisions and potentially make changes in their own actions.

Given particular emphasis within the exhibit was Picasso’s Guernica, 1937, which I believe is aptly representative of this time within Picasso’s artistic life.

While the museum did not display the image, since it is a mural, a large projection was shown in addition to an amazing chronology of the construction and development of the final product. There is much controversy surrounding the potential meaning and symbolism of the image, however as a simple response Picasso stated,

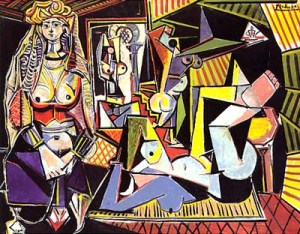

There was some discussion of Picasso’s found object sculpture and collage work being a combination of both the world of the elite artist and the life of the poor, however I ignored most of this discussion and just focused on what I was looking at. It would seem Picasso wasn’t too interested in this topic either, because in the next phase of his artistic development he attempted to determine his place within the artistic elite by interpreting the traditional masterpieces in his own manner. Through this experimentation, he would carve out a niche for himself within the well-respected professionals through direct comparison similar subject matter but varying stylistic techniques. Such an example is Picasso’s interpretation of Delacroix’s Women of Algiers from 1834.

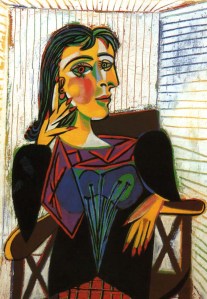

Having survived the museum experience, I picked up a postcard to commemorate the occasion (I have been doing so with all my museum trips) and selected the Ritratto di Dora Maar from 1937.

Since you have been wearing your thinking cap and your brain has been sufficiently fed from the healthy snack you selected previous to reading, can you tell me what phase of Picasso’s you would classify this painting as?

In general, I was impressed with the exhibition. Paula and I had tried to go on a weekend but found the lines too intimidating to conquer. After being denied by a closed Triennale Design Museum, we decided to check this museum and found it open on a Monday, to our great surprise (museums here are typically closed for Mondays)! Unfortunately for us, every student tour ever to be scheduled was also viewing the collection that Monday morning. This would have been no great challenge, had a group of 12 year old boys not decided to try out their English speaking skills. Even more unfortunate were their choice of words. Starting in whispers and increasing in volume to a small shouts, Paula and I endured the phrase “F**k me” coming from all directions while we tried to observe the masterpieces. At some point I finally broke from our concentrated ignoring to flash a glare and go in hunt of their teacher. While I couldn’t find her immediately, she was short, I think I did scare the rebels into silence because afterwards we were rewarded with a much more pleasant viewing experience. Curse free.